I apologise in advance for the length of this post. it is an almost verbatim coverage of my talk at Palmstead on 24th January. The actual presentation can be downloaded from the Palmstead website.

Come gather ’round people Wherever you roam And admit that the waters Around you have grown And accept it that soon You’ll be drenched to the bone. If your time to you Is worth savin’ Then you better start swimmin’ Or you’ll sink like a stone For the times they are a-changin’.

Lyrics from Bob Dylan’s ‘The times they are a changing’. I don’t think that there is a single person that doesn’t think times are changing. On almost every aspect of life, the world is changing around us, sometimes bewilderingly and often unpredictably. Often this feels threatening – we are programmed to be suspicious of change. Our survival relies on understanding the world, and if the world changes, then we find the unpredictability dangerous.

But change also offers opportunity. Businesses which do not adapt to change struggle to survive. Those that exploit change to their advantage thrive. The rest of us play catch-up. This article is about what opportunities change can bring us. But first of all, I want to look at how we got to where we are.

A short History of Urban Design(Looking especially looking at housing and landscape)

As I sit in my office and look out of the window, this is what I see: a new housing estate. This is what we all want. It must be, because we buy them by the thousand (and for a lot of money). But where are the trees? Why is it that most house-builders are so against planting trees? In fact, why are they generally against putting landscape in place? (Looking especially looking at housing and landscape)

We have all seen the dwarf conifers and Choisya ternata sundance around show homes, and the poor apology for gardens. Most of them are barely big enough to put a shed in. And yet, it seems to me that the most expensive, the most sought-after areas of housing are dominated by something larger than the houses – trees. And not just any trees; large, mature, forest species – horse chestnuts, oaks, planes trees, limes, even sycamores. So clearly, green leafy suburbs are what we really want. In fact, the media frequently use the word ‘leafy’ as a synonym for affluent when they are talking about neighbourhoods.

If we trace the roots of housing development back 100 years or so ago, we come to the genesis of large-scale housing development the garden city movement. During the Victorian era, most development had been urban. At both ends of the social scale, mass housing as a concept had really only come into being at the beginning of the C19th, with developments such as Bath and the Nash terraces in London for the wealthy and mass terraced housing for the working class.

Interestingly, if you look at Victorian terraced housing in areas where land was cheaper, they still stuck to the urban model (such as in the back to backs in some Yorkshire villages). Sometimes the built the same houses but made the gardens longer. The terraced housing in Hitchin, where I live, has plots that are only 15-20 feet wide but between 100-200 feet long.

But the rise of a middle class in late 19th century England meant that a different demand started to emerge. The landed gentry wanted their town houses to be elegant and urban – gardens were not a part of that.

The working classes could only afford back to backs. Whilst the middle classes could afford more in terms of housing, they could only afford one house. What they hankered after was mini version of the country estate. Both the architecture and the gardens point towards this – half-timbered houses evoking an idealised view of Elizabethan country houses; lawns, which had previously only been the reserve of the very wealthy, became available to all with the invention of the lawnmower in the C19th.

The garden city movement pulled many of these threads together. This is an early plan of Letchworth, the first ‘Garden City’. It distilled elements form the arts and crafts movement (with which it was closely allied), social reform (particularly of the Quakers), town planning, and mixed all this with a heady dose of social idealism with which all great reform movements are imbued.

The garden city movement has acquired a new relevance in the last few years, since the Government referred to it in the Nation Planning Policy Framework or NPPF, published a five years ago. Paragraph 52 says: “The supply of new homes can sometimes be best achieved through planning for larger scale development, such as new settlements or extensions to existing villages and towns that follow the principles of Garden Cities.” And who could possibly complain about garden cities; they are like mother’s apple pie indisputably good. Well, I for one will complain. For me this is where it all started to go wrong. The fork in the road where it all seemed so nice led us after sixty years ago from Letchworth to the sort of crammed housing estates we are all so familiar with. One of the reasons that the Garden City idea was so popular was that it plugged into the English Dream. But continual watering down of that dream has made it into something of a nightmare.

Well, there is another way. By way of a contrast, I want to look at some higher density schemes in city centres. Let’s go back to those posh city-centre houses.

They may not have had gardens, but those houses surrounded big chunks of leafy landscape. This is Belgrave Square – courtesy of Google Earth. Dense development, virtually no houses, but lots of trees. The houses pay for those trees. Indeed, as I pointed out in my introduction to the SGD ‘Urban’ conference a few years ago, garden design started with urbanisation. Skip forward a hundred and fifty years or so.

It seems counter-intuitive to think that if you have more houses on a site you can have better landscape, but sometimes that is the case. This is a scheme that influenced me when I first started down the route to becoming a landscape architect back in the seventies: Lillington Street by Darbourne and Darke. Social housing for Westminster City Council c1961-62. Incredible to think that this was designed 60 years ago. Just keep these images and concepts in your mind, and we’ll come back to them later. But I spoke of changes and how they would affect us. There are a whole lot of different factors which are bearing on the current situation. Any of them on its own would be important, but together, there are irresistible changes that are underway.

First: Demographics – specifically, baby-boomers.

This is a group of people born in the post-war years, normally defined as between 1946 and 1964. As a group, baby boomers were the wealthiest, most active, and most physically fit generation up to the era in which they arrived and were amongst the first to grow up genuinely expecting the world to improve with time. They were also the generation that received peak levels of income; they could therefore reap the benefits of abundant levels of food, clothing, free university education, and pensions. The increased consumerism for this generation has been regularly criticised as excessive by the generations that came both before and after. So why is this relevant? Well – a few facts: According to the Resolution Foundation, baby-boomers own half of the Britain’s £11tn worth of wealth and assets. The report shows 82% of wealth increases between 1993 and 2012-14 were due to owning homes, with the gains amounting to a staggering £2.3tn wealth windfall. This generation is normally characterised as being more focussed on ‘ownership’ and goods rather than experience. However, most research shows that spending tails off with age, and that the percentage spent on things like holidays increases, whereas spending on capital items decreases. This has significant implications particularly when you think that this group has made up a major part of our client base over the last couple of decades. Actually, the shift towards experience is happening across all age groups but is more concentrated in the ‘Millennials’ as a group – which takes us to…

Millennials. There are no precise dates for when this cohort starts or ends; demographers and researchers typically use the early 1980s as starting birth years and the mid-1990s to early 2000s as ending birth years. As I mentioned a minute ago, this generation is typically said to be more focussed on ‘experience’ than ‘ownership’. This represents the conventional wisdom for Millennials (figures from the US, but the UK is similar). This is slightly misleading In fact, recent research shows that all parts of the population and economy are becoming more focussed on experience. This is often accompanied or reinforced by technology – as in the music industry – where the whole model has moved from ownership to experience in the last 10-15 years- expand. If you look at your local high street, you will see exactly what ‘experience economy’ means. The most observable effect is more coffee bars, barbers etc and fewer shops, although it is more subtle than that. Example. Research from Foxtons also shows that Millennials also tend to buy smaller apartments than they can afford, spending a higher percentage on other things (meals out, holidays etc) than previous generations.

But the main thing is the cost of housing.

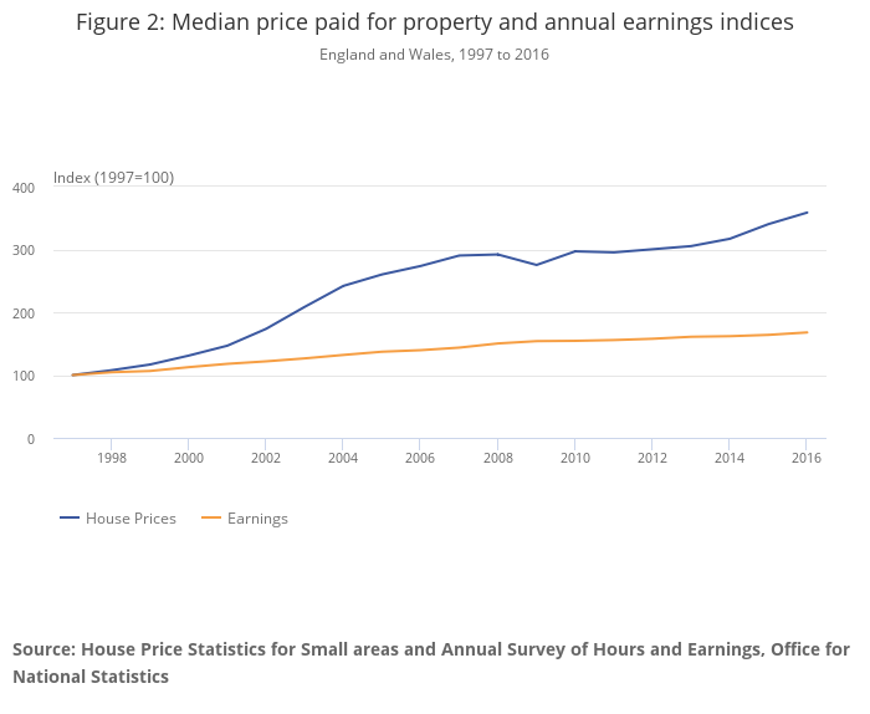

Houses have become significantly more expensive in the last twenty-five years, relative to income. This is hardly news to anyone here. There has been some softening in the last 18months or so, but the long-term trend has been upwards.

You can see from this graph the relationship between earnings and property for the whole of England and Wales. The dip in the recession in 2009 is clear and the pause in property and earnings rises can be seen up to about 2012, but thereafter it widens again. This means that across England and Wales as a whole, the cost of housing relative to earnings has roughly doubled.

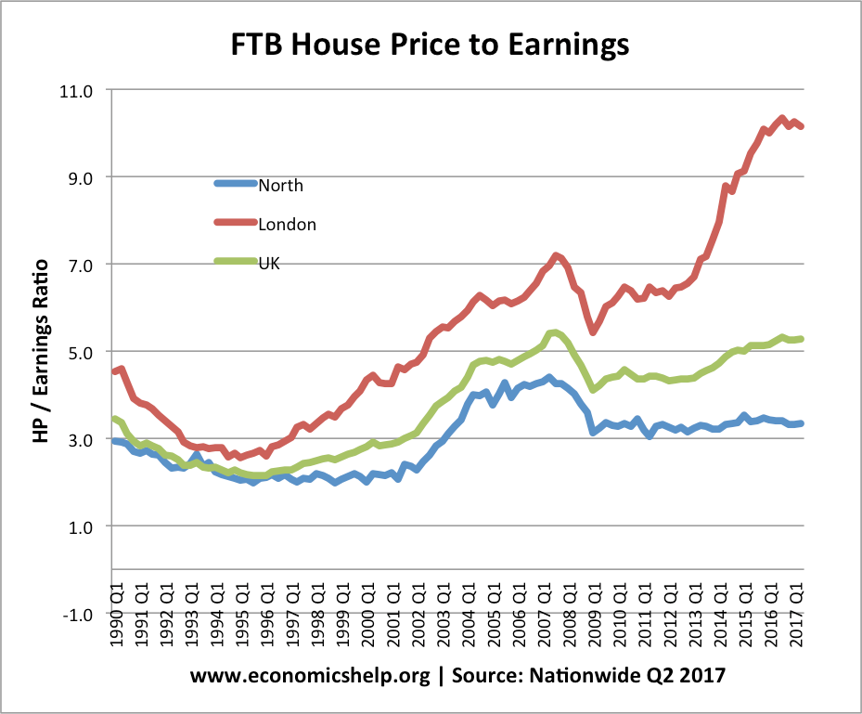

The trend for London (and the south east) is even starker. This makes it clear that the trend is regional. We don’t have a national housing crisis, we have a regional one.

But there is an interesting tail to this. The rise in rental prices is much steadier. This means that until recently, developers were ignoring the rental market because the yields did not stack up against the cost of borrowing. Even though high prices have reduced buyers from within the UK, there have historically been plenty from overseas. That market is less certain. Meaning developers are becoming increasingly interested in the build to rent market. I know several major developers who are moving their attentions from Build-to-sell for Build-to-rent – CapCo and Argent amongst them.

But there is a problem: there is a shortage of land. Let’s look first at what has driven land availability over the last three decades.

The first answer is structural industrial change. The O2 site and much of the Kings Cross redevelopment are both examples of former Gasworks site.

Of course, at Kings Cross they kept some of the gasholders. Much of the development along the riverside in London is a product of industrial restructuring, such as Battersea Power Station, or Tate Modern (also a former Power Station).

The second major driver is technology and consolidation – Port facilities moving downstream, telephone exchanges, rail yards, etc.

This is the Isle of Dogs before development,

and after; with plenty of opportunities for landscape. The final structural change is the moving tide of land values, which is obviously partly linked to the first two.

Wharf Road Gardens, King’s Cross

Often as at Kings Cross more than one of these factors works together. But it is important to consider that:

- Much of the structural change has now occurred

- Most of the remaining large plots of land are publicly owned.

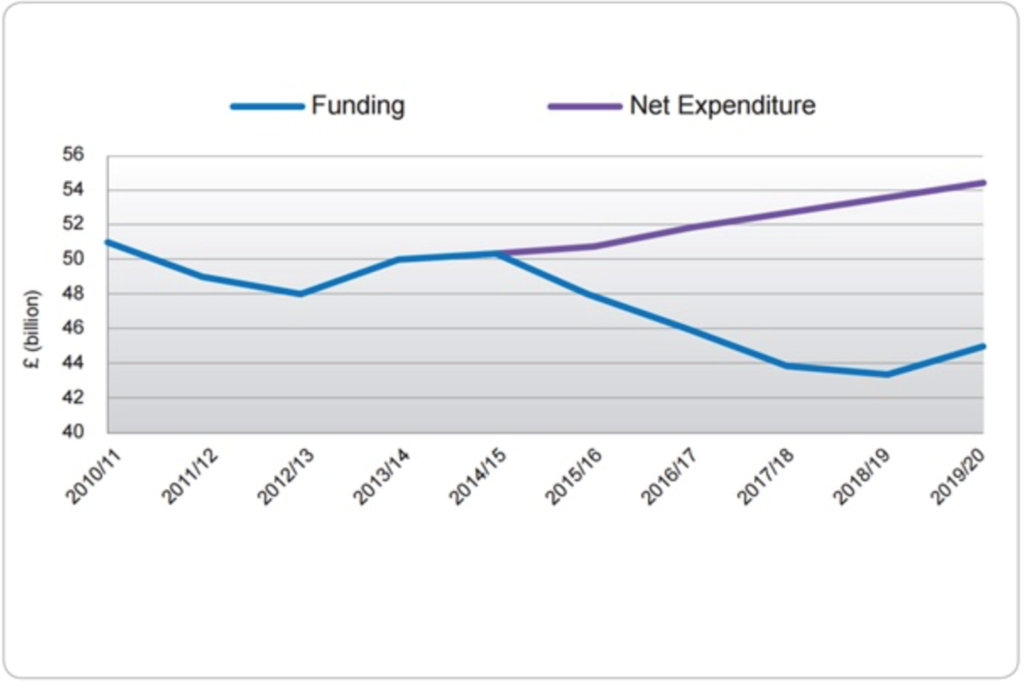

Which brings us on to the fifth piece of the jigsaw: Cash-strapped Local Authorities. Councils in the UK are not only cash-poor, they are income poor.

This is an interesting little – and slightly depressing – graph showing the divergence between funding and expenditure.

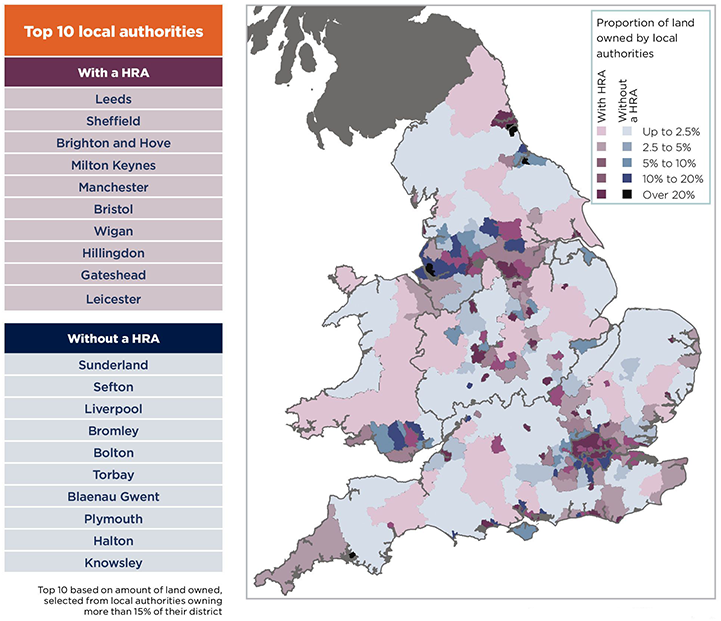

However, Councils are relatively asset rich This map shows land ownership in England and Wales, by percentage owned by local authorities. ‘HRA’ refers to Housing Revenue Accounts. In October, the Prime Minister announced that the Housing Revenue Account (HRA) borrowing cap for local authorities will be abolished with immediate effect in England. This removes one of the biggest constraints on council house-building.

Local authorities will now be able to borrow more money to invest in larger scale development and contribute significantly to the delivery of new affordable housing. We have estimated that councils could build at least 15,000 homes a year in the long term.

Lifting the debt cap only affects those local authorities with housing revenue accounts, about half of all councils. However, the implication of this is that because of years of austerity, local authorities lack the skills to carry out development. But you might remember that developers have all of the skills, but no land. Let’s go back to Kings Cross for a minute. Let’s go back to Kings Cross for a minute. This scheme worked partly because of a really good balance of assets and return – a long term partnership between the local authority and the developer that benefitted both parties.

Another well-known ‘partnership’ (this time in inverted commas) is the Lendlease-Southwark one. Many people feel that this is too one-sided, with the local authority not gaining as much form the deal as they could have. The proportion of council or social housing is low and it has effectively led to a diminishing in the local authority housing stock, at least locally. Lendlease tried the same sort of deal in Harringey, signing a £2bn agreement in Jan 2018, only for the council to back out in July 2018 citing: “the deal did not provide the answer to the challenges faced by the council”. The local authority also objected to the level of risk it claimed the JV indirectly exposed it to through its 50 per cent stake in the venture. Haringey Council added that it did not agree with the deal’s “approach to public assets”, as the agreement would see the council’s commercial portfolio move “out of 100 per cent public ownership”. So, getting the balance right is not easy for local authorities. In Haringey, the entire labour council fell and was replaced.

This somewhat idealised CGI leads us neatly into the final piece of the jigsaw. The Green Agenda.

You may not think that this is such a ground-breaker – it has after all been around for a while. Local Authorities have had a requirement for green infrastructure plans for some time now. There is a mass of evidence for the benefits. The real difference here is that Developers are beginning to move in the direction that this is something worth doing for marketing, rather than for planning, especially in the commercial property sector. Part of this goes back to the demographics. More and more employees are asking for a good working environment, so developers are anticipating that and pitching it to prospective tenants.

A quick example:

Tishman Speyer acquired this building about 5 years ago. We were initially taken on to design some monoculture planting around the edges of the terraces. However, to their credit (and following on from our amazing presentations!) the developer saw the possibilities. They were getting rid of lettable office space to make the terraces. In addition, they were surrounded by a huge development by Landsec which had the potential to completely swamp their development. They needed something to set their scheme apart and fixed upon landscape. they renamed it ‘Verde’ and marketed it as ‘The park in the sky’. This attracted higher quality tenants and they made a record profit on the scheme. The tenants in turn spent yet more on the terraces.

This was the pitch…

And this was the result (incidentally photographed from the site next door where we are also working).

So that is my jigsaw of the principle factors underlying the changes. But what are the overall implications of this, particularly in terms of the landscape industry, and are they positive or negative?

And what are the key learnings from all this?

- The rental market becomes much more important, particularly in the south and in cities.

- Developers will be moving more towards a build to rent model.

- They will therefore have a longer-term stake in the development, rather than looking for a short-term return on investment.

- This implies more consideration of ‘whole life’ costs.

- It also means that they will be interested in protecting their investment – they will have an interest in it continuing to look good.

- The economy moves more towards ‘experience’ than ‘ownership’, particularly in younger age groups. Millennials want to spend a greater proportion of their income on ‘experience’ rather than ownership. What are the practical implications of this to landscape?

- Smaller apartments, more green space

- More public space – more restaurants, coffee shops, hotels, parks and squares;

- More attractions, holiday destinations, etc.

- Expect to see more public-private cooperation, though friction may result.

- Developers have a shortage of land, but a surfeit of skills ◦Local authorities have a shortage of skills, but are asset (land) rich and cash/income poor.

- Result – more public-private partnerships. But this is a minefield. Expect plenty of friction along the way. Ultimately central government needs to set some ground rules, but there are plenty of opportunities.

- Cross industry co-operation will be become more the norm. If you look at the really successful developments, there are a result of close collaboration and partnership. Not only between public landowners and developers, but also across the disciplines – contractors, landscape architects, urban designers and master-planners, garden designers, nurseries etc. Cooperation and partnership increase value, increases quality and makes for a better experience for all concerned.

- The green agenda becomes universally more important.

- More important to planning authorities

- More important to consumers

- More important to developers

The lessons?

- Flexibility of approach is key – don’t stay hitched to one model.

- Cooperation and partnership increase value, boost quality and make for a better experience for all concerned.

Cars…

I’d like to kick a curved ball now to finish: the automobile. The car has come to completely dominate our lives from the second half of the twentieth century onwards. Is this about to end?

These two photographs were taken only 13 years apart – the impact of the car is clear.

Cars along the side of streets are a common sight in most of our cities. Whilst the introduction of electric cars does not alter this situation significantly, other than by reducing pollution (which is welcome), the onset of driverless cars will. There will not be fewer car journeys made, but there will be much less roadside parking and the road infrastructure could well change. What opportunities are there?

This is a linear park over and expressway in Boston that I went to have a look at last year.

Closer to home, this is some of Nigel Dunnett’s work in Sheffield – part of the ‘Grey to Green’ initiative. This clearly demonstrates some of the possibilities for roadside planting. A bit like the Churchgate scheme – you make your own opportunities.